This is a slideshow presenting the history of Seattle University, the Northwest's largest Jesuit institution of higher learning. The essay was written by Walt Crowley based on his books, Seattle University: A Century of Jesuit Education and William J. Sullivan: Twenty Years/Seattle University President.

Seattle University, 1891-2001 -- A Slideshow

- By Walt Crowley

- Posted 12/08/2004

- HistoryLink.org Essay 7163

Seattle University traces its local roots back to 1891, when two Jesuit priests established a school for boys in the young city. Today, SU is the largest Jesuit university in the Northwest, with an average annual enrollment of 6,000. This slide show traces the evolution of one of metropolitan Seattle's most important and innovative institutions of higher learning. (Photo of Bannan Center, 1991)

The Society of Jesus was conceived at the height of the Reformation by a converted warrior and future saint, Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556, shown here). In 1540, he persuaded Pope Paul III to charter a small "company" thinkers and teachers to battle the Church's critics with words and ideas, not swords and arrows. Initially mocked with the name "Jesuits," these early "soldiers for Christ" included such famed intellectuals and missionaries as Saints Robert Ballarmine, Edmund Campion, Matteo Ricci, Francis Xavier, and Peter Claver.

Independent thinkers from the start, Jesuit missionaries clashed with the Catholic establishment and with imperial powers, particularly in Spanish America. The order was suppressed between 1773 and 1814, by which time the "Black Robes" had achieved new fame in North America as missionaries to and defenders of indigenous peoples. At the request of local tribes, Peter DeSmet, SJ, established the Northwest's first Jesuit mission, St. Mary's (shown here), near Missoula, Montana, in 1841. One of his successors, Joseph Cataldo, SJ, established what would become Spokane's Gonzaga University in 1866.

By now, Seattle was emerging as a major city. Its first permanent priest, Fr. Francis Xavier Prefontaine, pleaded with Cataldo to establish a school in his town. Although understaffed and underfunded, Cataldo approved purchase of a future campus (shown above, looking east from Broadway) on Seattle's First Hill for $18,382 in 1890. The following year, he dispatched two priests from Yakima to take over Prefontaine's struggling boy's school in St. Francis Hall (shown in the lower photo) on 6th Avenue at University Street.

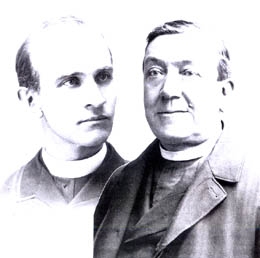

Victor Garrand, SJ, and Adrian Sweere, SJ, arrived in time to commence classes at St. Francis on September 1, 1891. The younger Garrand (b. 1847, left) and more seasoned Sweere (b. 1840) jumped into their duties with enthusiasm, aided by the Sisters of the Holy Names. When not teaching, they struggled to raise enough funds to build a new school on the First Hill campus.

Despite the relatively small numbers and poverty of Seattle's Catholics -- and the economic depression of 1893-1897 -- the Jesuits succeeded in constructing a handsome stone and brick school house and chapel near the corner of Broadway and Madison Street. The new parish and school opened on December 8, 1894, the feast day of the Immaculate Conception for which they were named.

Sweere was reassigned to Yakima soon after the school opened. Garrand fell ill with typhoid in 1896 and was sent east to recover (he ultimately died in Africa in 1925). Sweere returned the following year, and rechartered the school as "Seattle College" on October 21, 1898. Within a year, the school was offering high school classes to 137 boys. In 1900, it opened its first college-level course.

Sweere also pursued development of the Immaculate Conception Parish, and guided construction of its imposing church at 18th Avenue E. and E. Marion Street. He departed for other missionary work soon after its dedication in 1904, and died in Alaska in 1913. Meanwhile, his school was nearly lost in a disastrous fire on May 1, 1907.

Sweere's successors* expanded Seattle College's college instruction and drafted ambitious plans for the campus. The fledgling institution granted its first bachelor's of arts degrees on June 23, 1909, to John Concannon, John Ford, and Theodore Ryan. James R. Daly earned a Master's of Arts degree the following year, but the college program never attracted more than a handful of students.

In this photo, SC students hail "The Freshman" in a school play, but there were few real ones on campus. Military duty and high-paying jobs during World War I siphoned off the last enrollees by 1918, and Seattle College suspended higher level classes.

*The Jesuit injunction against "inordinate attachment" mandated rapid turnover of college presidents for several decades.

Old conflicts also complicated life for the College. Bishop Edmund O'Dea (shown here), who built St. James Cathedral in 1907, resented Jesuit competition with Diocesan schools and coveted its second, more prosperous parish, St. Joseph's on Capitol Hill (a third parish, Our Lady of Mount Virgin, was established in 1911 to serve local Italian immigrants). Bishop O'Dea became alarmed when he learned that Seattle College president Joseph Tomkin, SJ, was planning a dramatic move north.

In 1919, Thomas C. McHugh, who had grown rich canning fish, approached Fr. Tomkin with an audacious idea. He had learned that the small but modern campus of Adelphia College (an independent Swedish Baptist school founded in 1905), was facing foreclosure. He offered to pick up the cost of moving the college north to Interlaken Boulevard, and Tomkin leapt at the idea. Despite O'Dea's protests, Seattle College reopened in its new quarters (shown here) in September 1919. The original campus was all but abandoned.

Seattle College was again primarily a high school, but Tomkin's successor, Geoffrey O'Shea, SJ, was determined to rebuild the college program. In 1925, Seattle College granted its first baccalaureates in nearly a decade to Howard LeClaire, Henry Ivers, and George Stuntz. Its program was overshadowed, however, by the giant University of Washington across Portage Bay, and the mingling of high school and university instruction alienated applicants. A separation of the two campuses was imperative. In this photo, Babe Ruth swats a few balls during a campus visit in 1925.

With funds from PACCAR founder William Pigott, Seattle College nearly purchased a large tract in Northeast Seattle, but it dropped the plan after the Stock Market crashed in October 1929. New president John McHugh, SJ, decided to reopen the First Hill campus, and dispatched Louis Egan, SJ, to clean up its derelict buildings and grounds. He worked fast, and five Jesuit instructors greeted 46 students on the morning of September 14, 1931.

Of this "home-coming" faculty, the most creative and popular was a young psychology professor named James B. McGoldrick. A native of Ireland, McGoldrick had little patience with bureaucracy, including that of the Church and his own order. He defied both in 1931 by offering "extension" classes to nuns and, soon after, lay women, at a time when co-education was still rare in Catholic schools. When officials demanded that McGoldrick end the experiment, he replied "Then, I'll dismiss the boys."

He won the standoff, and Seattle University is widely regarded as a pioneer in Jesuit co-education. McGoldrick is pictured here with an "outlaw" co-ed student in the 1930s.

Seattle College enrollment grew quickly during the 1930s under the guidance of a remarkable community of skilled Jesuit educators and administrators, including Raymond Nichols, Daniel Riedy, Howard Peronteau, John Balfe, Leo Schmid, Francis Logan, and Edmund McNulty. It recruited its first female instructor, Sister John Gabriel, who developed the School of Nursing with the Sisters of Providence, and named its first Dean of Women, Anna Proutz. Father McGoldrick established its first discrete school, for Education, in 1935, and the College secured full accreditation the following year. The SC Jesuit community is shown here in 1936.

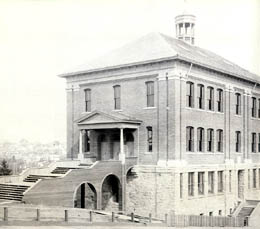

In 1938, the college team, Maroons, adopted a new name, Chieftains, suggested by student sports writer Ed Donohoe, feisty future editor of the Washington Teamster. Enrollment topped 1,000 in 1939, and the College launched construction of its first major new building, Liberal Arts (shown here, now Administration), in 1940. It was dedicated only a few months before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The college shifted to a war footing under president Francis Corkery, SJ, strengthening programs in engineering, nursing, and other fields of military value. He was succeeded in 1945 by Harold Small, SJ, who faced the daunting task of housing a post-war enrollment swollen to 2,400 by returning veterans and the G.I. Bill. Every square inch of the campus sprouted war-surplus portable buildings (shown here in 1948), while decaying First Hill mansions were converted into dormitories. After decades of struggle, it seemed that success might be Seattle College's final undoing.

A new direction and a new school name arrived in 1948 with Albert A. Lemieux, SJ (b. 1909), a handsome young priest from Montana. The 15th president of Seattle College became its "last" on May 28, 1948, when Lemieux announced re-incorporation of "Seattle University."

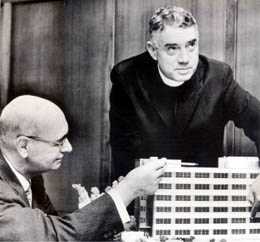

The charismatic Lemieux reached out to wealthy Catholic donors such as Paul Pigott and Thomas Bannan (shown here, left) to fund new classroom buildings and dormitories. He also expanded the University's outreach to minority students and non-Catholics, and raised its profile in the general community through public service and television appearances. He encouraged new programs, such as an expanding curriculum on alcoholism guided by James Royce, SJ, and organized a lay Board of Regents to help guide the University.

Lemieux's efforts were boosted by the success of the school's basketball team in the early 1950s. Coach Al Brightman recruited a remarkable pair of brothers, Eddie (left) and Johnny O'Brien, who led the team to its first NCAA tournament in 1953. They were followed by other great players, including Elgin Baylor, Eddie Miles, "Sweet Charlie" Brown, and Tom Workman. The Chieftains narrowly lost the 1958 NCAA championship in a season later tainted by scandal. Other SU notable athletes of the 1950s and 1960s include golfer Pat Lesser and tennis aces Janet and Steve Hopps and Tom Gorman.

The 1960s began with a dramatic liberalization in Church practices and philosophy under the guidance of Pope John XXIII and the "Vatican II" Council, and election of the nation's first Catholic president, John F. Kennedy. Seattle University responded by intensifying its outreach to the Central Area community, expanding its lay faculty, and building ecumenical bridges with Jews and other non-Catholics. SU also acquired its first computer system and reorganized its core curriculum, but the latter proved to be a financial time bomb.

In this photo, Rabbi Raphael Levine presents a B'nai B'rith award to Fr. Lemieux.

Lemieux retired in 1965 and was succeeded by Jack Fitterer, SJ, shown here (left) with SJ Superior General Pedro Arrupe during a 1966 visit to SU. Fitterer was the model of a "modern" Jesuit, who extended SU's community outreach and service. He proved less able, however, as a fund raiser and manager, and he embroiled the University in an embarrassing conflict with its neighbors over public access to its expensive new Connolly Gym. Fitterer also proved less than effective in handling an increasingly vocal and politically restless student body energized by the issues of the later 1960s.

Fitterer departed in 1970, but his successor, conservative theologian Kenneth Baker, SJ, fared even worse in addressing the political and fiscal challenges of the day. His public comments and attempts to discipline student protesters, shown here in May 1970, divided the University and alienated potential supporters and enrollees.

Baker resigned after only 10 months, and was succeeded by veteran Jesuit educator Louis Gaffney, SJ, who preached "contagious optimism," restored peace to the campus, and rebuilt scorched bridges to the community by adding the first lay members to SU's formerly all-Jesuit Board of Trustees. Gaffney also encouraged innovation, including a pioneering degree program in software engineering created by Frank Wood, SJ.

Gaffney's self-imposed five-year term limit expired in 1975, and SU welcomed Edmund Ryan, SJ, (shown here) an energetic reformer from Georgetown University. He in turn recruited a young William Sullivan, SJ, from St. Louis to guide academic development. Ryan launched a series of new initiatives, but his health failed after only a year.

Bill Sullivan became Seattle University's 20th president on May 3, 1976, and immediately recruited Fr. Lemieux (right, upper photo) to serve as Chancellor. He pushed ahead with new programs, such as the Matteo Ricci College and SU's first MBA program. Sulliavan also raised the University's public profile by inviting world leaders such as the Dalai Lama to speak on campus, and by helping to lead community projects such as the 1990 Goodwill Games. He promoted women's athletics while withdrawing the faltering men's basketball team from NCAA competition. Fr. Sullivan (shown in 1991 in the lower photo) also launched a new effort to revive and preserve SU's core Jesuit values as its lay faculty and non-Catholic enrollment expanded.

Sullivan also pursued an aggressive program of capital planning and fund raising, aided by donors such as Gene Lynn, Genevieve Albers, Theiline Pigott McCone, and the Casey Foundation. The campus was transformed during his tenure with construction or expansion of classroom buildings, including restoration of Seattle University's original home, Garrand Hall.

Following celebration of the University's centennial in 1991, Sullivan launched a new capital campaign, which raised more than $60 million for yet more improvements. These included a campus chapel dedicated to Ignatius, dramatically realized in 1998 by architect Steven Holl. Sullivan ended his 20-year tenure by accomplishing another long-held SU goal with acquisition and relocation of the University of Puget Sound's law school program.

Fr. Sullivan is shown here with SU faculty on his retirement as president in 1996.

Steven Sundborg, SJ, took the president's chair in September 1997, while Sullivan, although slowed slightly by a stroke, assumed the role of chancellor. This dynamic team has pressed ahead with campus improvements, including the law school's new home in Sullivan Hall, and academic innovations to better serve its 6,000 students.

In respect to Native Americans, SU retired the "Chieftains" team name in favor of the "Redhawks." in 2000. Sundborg also extended SU's outreach into the local and world communities by hosting such distinguished South African leaders as Bishop Desmond Tutu, former president Nelson Mandela (left, upper photo), and his wife and fellow activist Graca Machel.

In its 110th, Seattle University remains faithful to the Jesuit missions of intellectual inquiry, education, and community service. Fathers Garrand and Sweere would no doubt approve.

Sources:

Walt Crowley, Seattle University: A Century of Jesuit Education (Seattle University, 1991); Crowley, William J. Sullivan: Twenty Years/Seattle University President (Seattle University, 1996).

Licensing: This essay is licensed under a Creative Commons license that encourages reproduction with attribution. Credit should be given to both HistoryLink.org and to the author, and sources must be included with any reproduction. Click the icon for more info. Please note that this Creative Commons license applies to text only, and not to images. For more information regarding individual photos or images, please contact the source noted in the image credit.