This is a slideshow photo essay on the history of Seattle's Kingdome, its site, design, and construction. The Kingdome (formally, the King County Multipurpose Domed Stadium) opened in March 1976 and was imploded in March 2000. Written and Curated by Heather MacIntosh.

Kingdome: A Slideshow History of its Site, Design, and Construction

- By Heather MacIntosh

- Posted 11/17/2004

- HistoryLink.org Essay 7048

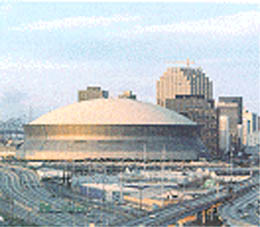

Even before its construction began in 1972, Seattle's domed stadium, the Kingdome, was one of Seattle's most controversial buildings. The history of the site and the building's construction provide critical perspective to this much maligned, and to some, beloved city landmark. The Kingdome stands (and falls) in the wake of decades of changes -- economic, political, social, and cultural -- that have shaped Seattle's public identity.

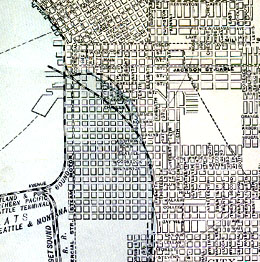

The Kingdome's location played a major role in the controversy that protracted construction. The King Street site, just south of Pioneer Square, was chosen after voters rejected putting the Dome at Seattle Center. During the course of the 12 years during which the Kingdome's site was debated, King County considered more than 100 potential sites. The history of the eventual construction site was a critical part of the stadium's story, both before and after it was built.

This particular patch of downtown Seattle was 30 feet under water at the turn of the twentieth century.

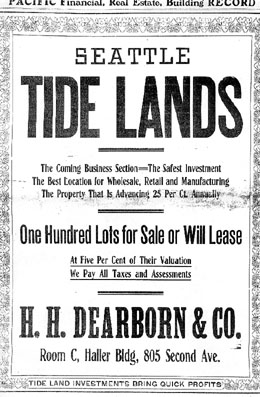

These natural conditions were history by the early twentieth century when the seductive possibilities of real-estate development in Seattle engrossed investors. This attraction quickly transformed the virgin forest land into a bustling town whose primary income came from timbering and coal mining.

On the shores of Elliott Bay, investment companies soon built infrastructure to support these industries. The resulting network of piers and railroad tracks soon reached out into the water, competing for space on the choked waterfront.

These first railroad, transportation, coal, and general "improvement" companies opened the door for larger regional and national concerns, like railroad giants Northern Pacific, the Great Northern, and the Union Pacific. The promise of a transcontinental railroad terminating in Seattle titillated speculators who eyed the city's tidelands then transected by wooden piers and trestles.

At the same time, Seattle sought to improve its streets and to level its hilly topography. "Business didn't travel uphill," or so they thought when horses were the primary means of transportation. A series of regrades tamed much of city's once steep terrain, including Jackson Street, leveled in 1906. The dirt from the regrades filled the tideflats lying at the base of Jackson Street, and provided several square miles of flat new land.

The Union Pacific's E. H. Harriman sent a representative to Seattle in 1907 to purchase land for the station and rail yards. This provoked a real-estate frenzy in the tidelands, most of which were owned by Ralph W. Dearborn. Great Northern President James Hill completed his Union Depot on King Street in 1906. Construction on Harriman's Union Station began a few years after. By 1911, the freight yards near the station supported four transcontinental rail lines.

Soon after the construction of both stations, rail traffic began a steady decline both locally and nationally. With the exception of a brief spike of activity during World War II, the freight yards and the stations saw dwindling use. Railroad Avenue, which once dominated the waterfront, was paved over in the mid 1930s for Alaskan Way. The Alaskan Way Viaduct was completed in 1953.

In 1970, when Amtrak began service, Union Station closed and the surrounding neighborhood stood desolate. The nearby International District had grown since the Jackson Street Regrade into a strong and cohesive community of businesses and residences. Members of this community, fearing the consequences of a civic behemoth in their backyards, fought the County as it settled upon the freight yards site for the new multipurpose stadium.

The land was commercially fallow, and relatively cheap for a site so close to the city's center. Economy was paramount, influencing the construction and design of the building conceived as a new Seattle icon.

The project, initially budgeted at $40 million in 1968, was significantly underfunded by 1972 when design began, due to rising interest rates and inflation.

The Kingdome's designers and engineers were forced to make the most of a bad financial and political situation. They worked long hours to meet the deadline to call for construction bids, and they sweated every element so that each served more than one use.

Other domed stadiums in New Orleans and Houston had already been built for much less, thanks to good timing. These had steel truss domed roofs and major league ball teams. In 1972, King County had no major ball teams, not enough money, and 12 years of public debate behind the project.

The controversy surrounding the stadium took its toll on its design and the designers and contractors who built it. Siting debates extended the building's schedule and siphoned money away from the budget to pay for law suits and administration to process the flood of gripes generated by active and outspoken groups of citizens.

Foremost among the disgruntled was Frank Ruano, caricatured as Don Quixote on the cover of The Seattle Times Magazine on June 19, 1977, along with a windmill bedecked Kingdome.

The design, born in this stew of contention and financial limitation, was innovative, and not only because it was the largest concrete dome in the world. It set several other records in the field of stadium design: 1) it was the least expensive domed, air-conditioned stadium of its size in the world; 2) design and engineering took only six months; and 3) their contract bid was only .05 percent from their estimate.

Dull stats indeed for a building with such a high public profile.

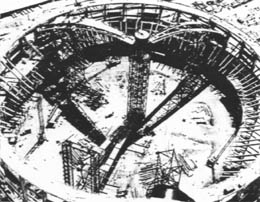

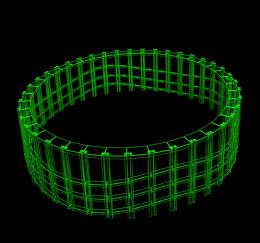

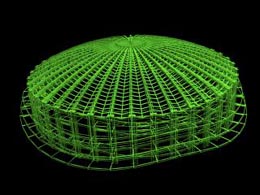

The stadium's enormous concrete dome required an extraordinarily strong structural system. Structural engineers and architects solved this problem by fusing a system of piers with rings of reinforced concrete.

These rings would become the most distinctive element of the building's profile (resembling a layered hamburger with a concrete bun). The combination of piers and rings provided for the tremendous outward thrust caused by the weight of the concrete dome. The bands allowed for 8.8 million pounds of tension, which included support for lighting (360 tons), a gondola for instant reply screens (20 tons), and snow load (4,600 tons). The dome also had to withstand earthquakes.

The scope of this project was enormous. The Kingdome covered 9.1 acres, and used 52,800 cubic yards of concrete. The building contained 443 tons of structural steel. It accommodated 64,722 football fans, 59,623 baseball fans, and 80,000 "personality show" attendees. This was almost triple the capacity of Sicks' Stadium, Seattle's open-air ball park that the Kingdome replaced.

The Kingdome's meager budget, siting issues, and design collided in the Kingdome's construction.

Building the monumental concrete structure was complicated, initially requiring 260 contractors and subcontractors including 100 carpenters, 30 to 40 laborers, 30 to 40 operating engineers, seven surveyors, 27 iron workers, three electricians, three plumbers, and a team of cement workers. During the dome's construction, 60 more contractors joined the effort. The picture shows Donald Drake Company employees key to the stadium construction: Gail Taylor, Office Engineer; Ray Biggs, Project Manager; and James Gorman, Project Engineer, ca. 1974

In this image, taken in the summer of 1972, County Executive John Spellman (left) and County Councilman Robert Dunn (right) ceremonially extract the first railroad spike. Public watchdog Frank Ruano (1920-2005) stands to the far right wearing a sign of protest. The ceremonial spike, which Spellman proudly displayed in his office, was stolen during a riotous break-in months later.

On November 2, 1972, during official groundbreaking ceremonies, 25 young International District residents hurled mud balls at the event. On November 14, demonstrating residents continued to protest the stadium. International District resentment continued throughout the four-year construction period, resulting in a law suit and ambient ill will.

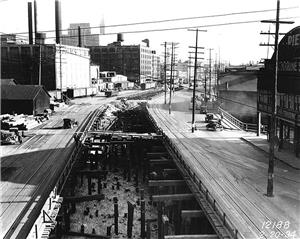

Contractors began excavating the site in late 1972, putting infrastructure in place, such as these pipes shown in a December 1972 photograph. Working with a woefully small budget and an already delayed work schedule, construction dragged.

The next step included setting rebar columns into a ring that would consitute one of the primary elements of the stadium's structural system.

Tragedy struck in January 1973, only months after construction began. One of the tall rebar towers fell on a workman while the rest toppled like dominoes. The workman was hospitalized. The accident was attributed to a broken turnbuckle.

The drooping supports raised eyebrows, and soon other design issues came to the fore. The contractor, Donald M. Drake, and the County's designers bickered over responsibility for the enormous falseworks. Falseworks such as structural scaffolding are members that support a dome or roof before the actual supports can do the job. The central falsework tower was 250 feet tall and contained 1,140 tons of structural steel, more than an average downtown office building of the period. The question of liability for this mammoth structure was not satisfactorily answered, and on November 22, 1974, Drake stopped work.

The falseworks were a necessary part of the dome's construction. The dome was a combination of precast and cast-in-place elements. The shape of the precast elements (ten different shapes in all) complicated the already monumental process. There were very few right angles, making connections between panels and cast-in-place elements more difficult. The dimensions of each of the sliver-shaped roof elements was smaller on the inside than on the outside.

The structural integrity of the innovative concrete dome, the largest of its kind ever built even today, was also in question. John Skilling, a partner in Skilling, Helle, Christiansen & Robertson structural engineering firm, publicly announced that the ribs were fine and would perform as predicted. The dome's design was extensively tested by computer. Its strength lay in its design, the engineers contested. It was a hyperbolic paraboloid, a double curvature, which allowed for an extremely thin concrete roof.

Drake continued his strike into December, incensing Spellman. The County Executive terminated Drake's contract on December 10, 1974, for being 300 days behind schedule and for failing at "basic performance." This opened another pecuniary can of worms as some balked at the additional expense involved in securing a new contractor. This photograph captures the stadium's progress up until Drake's walkout.

The County soon hired another contractor -- Peter Kiewitt Sons Construction Company, which started work on December 12, 1974. They addressed the falseworks problem immediately, and lowered and rotated them into position. Four of the 40 roof forms had been poured and left standing by Drake when Kiewitt arrived. The new contractors quickly assembled the remaining 36, in groups of four, and half were in place by mid-May 1975.

Despite optimistic projections, the stadium did not open in 1975, documented in this commemorative "Stadium 75" porcelain bottle, sold in local liquor stores in 1975. Besides this, 12,000 "Stadium 75" pins, were distributed starting in the fall of 1973. By mid-1975 however, the county realized the stadium would not open until the next year. Not missing an opportunity, the County simply deemed the Kingdome "Seattle's Spirit of '76." The building opened on March 27, 1976.

Licensing: This essay is licensed under a Creative Commons license that encourages reproduction with attribution. Credit should be given to both HistoryLink.org and to the author, and sources must be included with any reproduction. Click the icon for more info. Please note that this Creative Commons license applies to text only, and not to images. For more information regarding individual photos or images, please contact the source noted in the image credit.