This is a slideshow on the history of The Seattle Public Library. Written and Curated by Paul Dorpat.

Seattle Public Library -- A Pictorial History of Times and Tomes Past -- A Slideshow

- By Paul Dorpat

- Posted 1/01/1999

- HistoryLink.org Essay 7080

Seattle's first library association was organized in August 1868. Sara Yesler was appointed the first librarian, and this was more than a gesture to the family of the community's principal industrialist, Sara's husband Henry. Sara was a social activist on her own, and certainly a reader. After both Yeslers had died, their 40-room mansion at 3rd Avenue and James Street served as the city's library.

In 1869, the Library Association started a loan library. For pioneer towns accustomed to only churches or saloons for social life, the library represented an alternative for the community of readers. Among the titles listed for early acquisition by the association were Ralph Waldo Emerson's Essays and Percy Shelley's Collected Poems. The committee overruled its one member who objected that Shelley was a "freethinker."

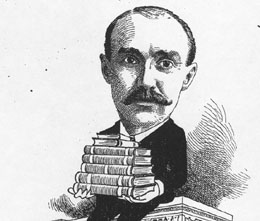

It was most likely economic opportunity that lured James McNaught to Seattle the year before he was made charter president of the Library Association. The erudite young lawyer was an unlikely pioneer who wore formal dress and campaigned for culture. McNaught, a prodigious reader, read through spectacles thick as bottles.

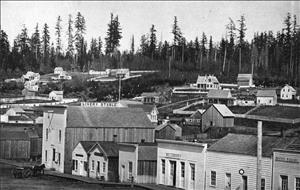

In the summer of 1873, the Library Association moved its meetings and reading room into the Yesler's new building at Front Street (now 1st Avenue) and Cherry Street (seen here on the right during the Big Snow of 1880). That fall, a large consignment of books arrived from San Francisco. Notices were posted inviting all to come and enjoy the association's reading room. However, by the mid-1870s the Young Men's Christian Association was caring for the books and providing most of the services.

After this transfer little is known of the library's activities until 1888 when the Ladies Library Association was organized at the home of Babette (Schwabacher) Gatzert at 3rd Avenue and Cherry Street. Seattle Post-Intelligencer owner L. S. J. Hunt and his wife gave considerable assistance. Yesler donated a lot, perhaps in memory of Seattle's first librarian, his recently deceased wife Sara Yesler.

Another activist in the library's revival was its recording secretary, Mrs. Adelaide Heilbron. Her father, W. H. Piper, had owned Boston's famous W. H. Piper Bookstore, where the lions of nineteenth-century American literature mingled -- Whittier, Lowell, Holmes, Longfellow, and Hawthorne. Young Adelaide grew up at their side, absorbing their wit and erudition.

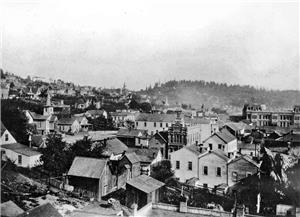

The city's Great Fire of 1889 delayed the opening of the association's library until April 1891, when a reading room was engaged on the 5th floor of the flat-iron Occidental Block facing Pioneer Square. The circulation department started later that year. In 1893, the library printed its first catalogue of books.

In the summer of 1894, the library was moved across 2nd Avenue to the fifth floor of the Collins Block at the southeast corner of James Street. Head Librarian John D. Atkinson directed a staff of five. In 1895, the library briefly instituted a policy of charging all borrowers 10 cents a month or a dollar per year.

When the library moved in February 1896 into the second floor of the elegant Rialto Building, all charges were dropped. The following year, the Frederick, Nelson and Munro Department Store would also secure a home in the Rialto.

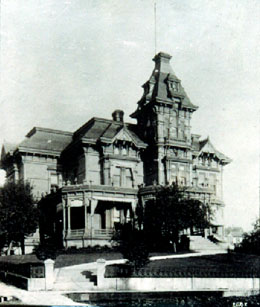

In 1899, the library moved again, this time taking over the Yesler Mansion. The Yeslers built their 40-room home in the mid-1880s and took residence in 1886. A year later Sarah Yesler, the community's first librarian, died suddenly of an illness diagnosed as "gastric fever." She was 65. Five years later the 82-year-old Henry Yesler followed.

Minnie Gagle Yesler, Henry's second wife (and second cousin) continued to live in the mansion with her mother until shortly before the library moved in and mounted its sign above the front porch.

Longtime librarian C. W. Smith set up his office in one of the bedrooms. The bindery was put in the kitchen, and another room was reserved for periodicals. A children's room and a reference department were opened. This still left more than 30 rooms for storage and for the stacking of the library's more than 25,000 volumes.

The all-wood Yesler mansion somehow survived the Great Fire of 1889, but flames found it 12 years later. Except for the books in circulation, the library's entire collection was destroyed along with the mansion in a fire that ignited at 1 a.m. on the morning of January 2, 1901.

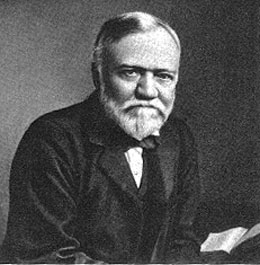

Three days after the Yesler mansion was consumed by flames, the steel magnate and library philanthropist Andrew Carnegie promised $200,000 for a new central library building. Carnegie later contributed another $20,000 for furnishings.

With the few books out on loan the night the fire burned the library down, the library relocated temporarily in the old Washington Territorial University building at the northeast corner of 4th Avenue and Seneca Street. Since the university had moved in 1895 to the new campus north of Lake Union, the old campus hung in a kind of extended public limbo, providing a temporary home for an assortment of events. It was handy for emergencies like the library fire. Soon, however, the library returned to the site of the fire and arranged its last temporary quarters in the old Yesler barn. In 1902, while seven trustees of the newly constituted Library Board were choosing a site for their new library and opening a competition for its architect, they were also fighting in Washington's Supreme Court for the contested right to have full power to control the library. On November 3, 1902, they won the case.

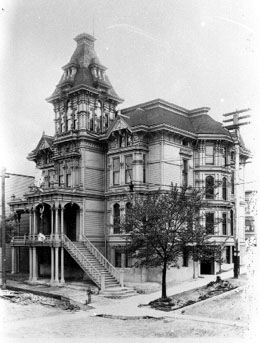

The board chose the site of the family home of charter founder James McNaught for its new library. James and Agnes McNaught had built their grand home in 1883, but by 1890 McNaught was Chief Solicitor for the Northern Pacific Railroad and lived with his family in another big home on the Hudson River near West Point, New York.

Soon after the McNaughts left Seattle, their mansion on 4th Avenue was converted into the clubhouse for the first exclusive men's club in Seattle, the still-extant Rainier Club. The city's power elite kept their clubhouse in the mansion until 1893, when it was converted into a boarding house.

The library's 1902 site decision required the McNaught's showplace to be destroyed or relocated. The choice was simple and so was the move. In 1904, the mansion was dragged across Spring Street to its northeast corner with 4th Avenue.

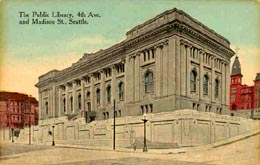

Before its completion, the new classical library was depicted on postcards as resting in a setting both pastoral and reflective -- nearly Edenic. The building was designed by Peter J. Weber.

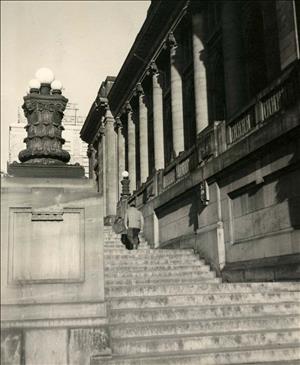

The actual site was on a rather steep hill fronted by wooden sidewalks and a dirty 4th Avenue. When its front door opened to the public on December 19, 1906, there was no need for a grand stairway. Within two years, however, construction on the Carnegie Library resumed as City Engineer R. H. Thomson directed the regrading of 4th Avenue.

At Madison Street, 4th Avenue was lowered 10 feet. One block north at Spring Street, it was lowered two feet more. In this view the new library, far right, and its neighbors -- continuing down the street -- the McNaught mansion, the First Presbyterian Church, and the Lincoln Hotel at far left, were all transformed into structures one story taller than they had been before the regrade.

For the library, this required the construction of a grand front stairway to reach the main entrance. Like the entrance to the modern library that replaced it, this was a popular meeting place throughout its half century of service.

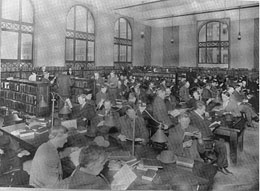

The central Carnegie Library was both solid and elegant, although, according to librarians who knew it well, not very practical. Just inside the front door, readers found themselves in a vaulting skylit lobby.

In back rooms, the bindery and mendery faced the morning light, which in later years was scattered by the ivy which draped the facade facing 5th Avenue.

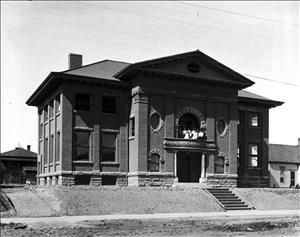

The Carnegie Library in Ballard was designed by Henderson Ryan and opened in the town of Ballard on June 24, 1904, when Ballard was still an independent town. Annexation in 1907 brought the building into the Seattle Library system.

Several other Carnegie-financed branches opened in Seattle neighborhoods following the dedication of the central library, and the architecture partnership of Somervell & Cote designed most of them. For the 1910 Green Lake Branch, the firm used what it described as a "modern French Renaissance style." It was also responsible for the design of the West Seattle branch, also built in 1910.

To fit the neighborhood, architects W. Marbury Somervell (1872-1939) and Harlan Thomas (1870-1953) chose a Tudor Revival (sometimes called English Scholastic Gothic) style for the Queen Anne Branch, which opened in 1913. In 1914 the two designed the Henry Yesler branch (later renamed Douglass-Truth) and in 1915 the Columbia City branch.

The last of Seattle's Carnegie libraries, the Fremont Branch (1921), was designed by Daniel R. Huntington and has little in common with the others. Totally unlike the symmetrical Beaux Arts and the Gothic schemes that had dominated Seattle library design, the Mission-style Fremont Library was outfitted with Stickley Arts-and-Crafts lounge chairs built by McNeil Island prisoners.

In its new and grand Beaux Arts landmark, the Central Library began adding departments and services, including in 1907 a periodical room, and a Fine Arts Division. Also that year, the first embossed books for the blind were circulated and several deposit stations opened around town -- 19 of them in fire stations.

From the homebase of its new home, the library provided a variety of satellite programs including small lending libraries sited in city schools and neighborhood businesses, visits to local hospitals,and story readings in community parks and playfields. Even a sandbox at Collins Playfield offered a comfortable venue for rapt attention.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the Library's free services were especially popular. The warmth of its shelter in the cold months was also appreciated -- and still is. In 1935, workers at the library took comfort themselves with the formation of the Seattle Public Library Staff Association. Organizing eventually led to their inclusion in the city's pension system and the return of salaries to what they were before the Depression. And in 1936, library staff won the 40-hour work week. In 1946, a Business Department was added for post-war enterprise, and the film library was inaugurated with the purchase of 57 documentaries.

The Wilmot Memorial Library in Wallingford was located in a house at 4422 Meridian Avenue N., a 1948 gift from Alice Wilmot Dennis in memory of her sister, Florence Wilmot Metcalf. It became the Seattle Public Library's 11th branch, and will serve the Wallingford neighborhood for 36 years.

When it was new, the Central Library was considered one of the grandest products of Carnegie's philanthropy. But 50 years later Kenneth Colman, chairman of the citizens for the successful library bond issue, described it as "a community eyesore, not fit for a progressive and forward looking city like Seattle."

Structurally the library was not so sturdy. The exterior walls contained no steel or reinforced concrete framing, but relied for cohesion on the strength of the mortar joints. Consequently the earthquake of April 13, 1949, damaged the library considerably, although not enough to cause its closure.

By the time of its destruction in 1957, years of weather had stained the library's sandstone facade. However, many readers loved the old building, including Japanese American photographer Koike, who took this pictorialist study of its entrance. Many considered the darkened patina on the library's exterior to be part of the building's charm.

The demolition of the old Central Library in 1957 was a slow and tedious process that involved a good deal of manual labor and crowbar work.

For temporary quarters the central library moved its stacks and services into the 7th and Olive Building, the old headquarters of Puget Power.

Dedicated in 1960, the modern library that replaced the Carnegie monument was designed by Leonard Bindon (1899-1980) and John L. Wright (b. 1916) in association with the firm of Decker, Christiansen & Kitchin. It was built in the then-popular International style and opened in 1960 on the same site as its predecessor.

The new library was well appointed with public art, including George Tsutakawa's Fountain of Wisdom, his first public commission.

We can imagine that founders Sara Yesler and James McNaught would have been thrilled by the variety of spaces and diversity of services offered in the new library.

Unfortunately, the central library did not age well and library growth soon far surpassed available space. Bonds for a new library were rejected by voters in 1994, but new City Librarian Deborah Jacobs launched a comprehensive community review in 1997. The effort was rewarded on November 3, 1998, when taxpayers approved $196.4 million in "Libraries for All" bonds. The Library Foundation pledged to raise another $60 million, and Bill and Melinda Gates donated one third of this sum in the largest gift to a public library in American history.

The Libraries for All plan included $119 million for a new central library on the existing downtown site. The plan also improved, expanded, or replaced 22 existing neighborhood libraries and constructed three new branches.

In July 1999, the Library Board selected the firm of avant-garde Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas to design the new 355,000-square-foot Central Library. It was a daring choice, guaranteed to create a singular structure. When the new library opened in 2004, it received world-wide acclaim, with the The New Yorkers' architectural critic hailing it as "first library of the twenty-first century" (The New Yorker, May 24, 2004).

Licensing: This essay is licensed under a Creative Commons license that encourages reproduction with attribution. Credit should be given to both HistoryLink.org and to the author, and sources must be included with any reproduction. Click the icon for more info. Please note that this Creative Commons license applies to text only, and not to images. For more information regarding individual photos or images, please contact the source noted in the image credit.