This is a Slideshow photo essay on the history of Seattle's Capital Improvement Projects. Written By Walt Crowley and curated by Paul Dorpat, with Chris Goodman. Presented by Seattle City Councilmember Martha Choe.

Building Seattle -- A Slideshow History of Seattle's Capital Improvement Projects

- By Walt Crowley

- Posted 11/16/2004

- HistoryLink.org Essay 7083

When Seattle's founders relocated from Alki Point to Elliott Bay in the spring of 1852, they settled on a patch of dry, level land framed by steep ridges on the north and east and by vast mudflats to the south. Thus, making the landscape more hospitable was a priority from Seattle's earliest days.

Seattle incorporated as a city in 1865, then dissolved, and then reincorporated in 1869. Village streets were built cooperatively and the community's first utility, its water supply, was developed by the the sawmill owner Henry Yesler. It delivered water from springs on First Hill first by an elevated flume down James Street and later by bored logs beneath it and other city streets.

After Seattle's second -- and successful -- incorporation in 1869, city officials began gathering public improvement funds from the usual sources, including taxes, licenses, and fines.

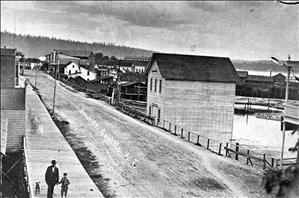

The community's first large-scale public works was also its first sizeable regrade. In 1876 Seattle leveled Front Street (now 1st Avenue) behind a timber cribbing north from Mill Street (now Yesler Way) to Pike Street.

Early City officials also wooed the Northern Pacific to help develop the city's harbor and transportation system. When the NP picked Tacoma for its Puget Sound terminus and company town in 1873, local boosters and agents for Eastern and Californian capitalists built their own railroads to connect Seattle first to the coalfields east of Lake Washington and to the outside world.

City fathers sweetened the deal with general waterfront franchises for both railroads and "mosquito fleet" steamers that made Seattle the principal port of call on Puget Sound.

To the south, a cooperation of public and private forces gradually filled in Pioneer Square's neighboring lagoons -- including the site of the Kingdome -- with trash, ship ballast, regrade fill, and dredgings.

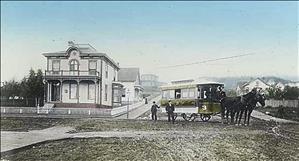

Most downtown streets were muddy tracks, so the city awarded a franchise to Frank Osgood in 1884 to build a horsedrawn streetcar line on 2nd Avenue. The city's "public transportation system" developed rapidly but remained privately owned and operated until 1919.

Many streetcar lines were built by early developers to spur "suburban" development in areas such as Ballard, Madison Park, and the University District. New public schools often followed the tracks, helping to establish Seattle's original "urban villages." This interplay of private and public investment continued to be crucial to Seattle's early growth.

In 1881 Seattle surpassed Walla Walla to become the largest community in Washington Territory. Eight booming years later most of its fire-trap business section was razed by the "Great Fire" of June 6, 1889. The city's private water system performed so pathetically through this inferno that Seattle voters approved bonds one month later to create a public water system.

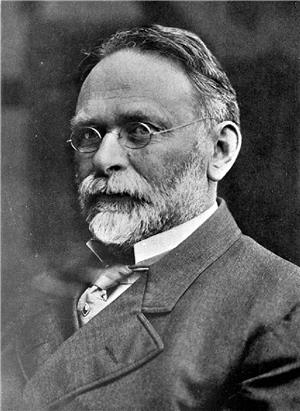

This was the first victory for a group of reformers, led by city engineer R.H. Thomson and others, who advocated "municipal ownership" of key utilities. At their urging, the city began acquiring the right of way for the first Cedar River pipeline in 1895, which was put in service in 1901.

By 1912 Seattle owned nearly two-fifths of the 143-square-mile watershed around Cedar Lake. The lake was later renamed the Chester Morse Lake for the water superintendent between 1938 and 1949.

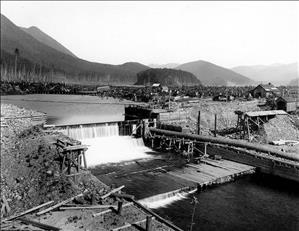

In 1902 Seattle also used the Cedar River to build the first publicly owned hydro-electric installation in the country. The new electric utility became City Light in 1910 and competed with private companies for customers until 1950, when it took over all service in Seattle.

David and Louisa Denny donated a former cemetery that became Seattle's first park in 1884 and now bears their family name. Seattle went on to develop a pioneering system of bike trails and hired the famous Olmsted Brothers in 1903 to plan an ambitious network of parks and boulevards.

City Engineer R.H. Thomson began leveling Denny Hill in 1899 in order to remove this "obstruction to the natural northerly expansion of the city." The "Denny Regrade" proceeded in fits and starts and was not completed until 1930.

In 1910, the voters created a Municipal Plans Commission and hired Virgil Bogue to create a vision of a future metropolis. Bogue's ideas, including a new Civic Center, proved too expansive -- and expensive -- and voters rejected his final plan two years later.

In 1911, King County voters approved a new Port Commission to wrest control of the waterfront from the railroads and return it to the people.

Also in 1911 the long debate on where to build a canal to link Puget Sound and Lake Washington was concluded. Construction began on the Ballard locks, later renamed the Hiram Chittenden Locks for the Army engineer who was both the first president of the Port Commission and guided the development of the canal to its 1917 dedication.

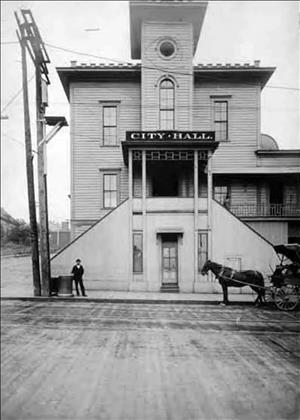

Much of Seattle's early development was guided from a hodgepodge of city offices dubbed Katzenjammer Kastle, while County offices occupied a large Courthouse on nearby Profanity Hill, now site of the Harborview Hospital Parking Garage.

The City and County joined forces to create a new building in 1916. It was expanded in 1930, but the City moved to its own Municipal Building in 1959.

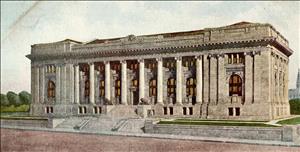

The City's first dedicated library was funded by the Carnegie Foundation and opened in 1904. It was demolished for a "modern" library in 1959, which is itself now slated for demolition.

In 1918, frustrated commuters approved buying out the private streetcar system. The City took charge on April 1, 1919, but the exorbitant purchase price ultimately bankrupted the Municipal Street Railway, and the streetcars were scrapped in 1941.

By the end of World War I, automobiles were displacing public transit as the fastest way to move people and goods. The State of Washington built the city's first "speedway" on Aurora Avenue, and ignored local voters by cutting a swath through the middle of Woodland Park.

Highway 99 was extended in 1952 with completion of the Alaska Way Viaduct, a structure that many later wished would sink into Elliott Bay. When the state began planning Seattle's "Central Freeway," now Interstate 5, city officials pleaded for a rail transit right-of-way but were ignored because it would cost an extra $16 million. Architects Paul Thiry and Victor Steinbrueck also proposed lidding I-5 through downtown, but this was not begun until construction of Freeway Park and the Convention Center.

In 1958, visionaries such as James Ellis proposed a new regional utility called Metro that could guide transit, water quality, parks, and growth management. Voters approved only the sewage treatment function, mainly because Lake Washington had turned into a smelly cesspool.

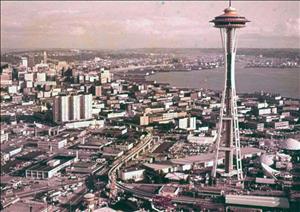

The Seattle World's Fair of 1962 reinvigorated public investment and created a lasting legacy in the form of Seattle Center. The Fair's totem, the Space Needle, was built with corporate funds, however, and remains privately owned.

Jim Ellis and his allies renewed their call for regional planning in 1968 with a set of 12 "Forward Thrust" bond issues, including rail transit. The rail plan failed, but voters approved a domed stadium and six other bond packages for parks and public facilities. A second set of Forward Thrust proposals all failed in 1970 during the "Boeing Bust" recession.

The 1960s spawned growing public suspicion of big highway and Urban Renewal projects. Neighborhood, environmental, and historic preservation activists joined forces in the early 1970s to save the Pike Place Market, cancel the planned R.H. Thomson Expressway, and downsize the I-90 freeway.

Voters finally put Metro in the driver's seat in 1972 by approving a sales tax for a bus-only regional transit system. By then, the City had come to rely heavily on federal funds for major projects such as rehabilitating Pike Place Market, but the federal budget was already beginning to creak under the twin demands of military and domestic spending.

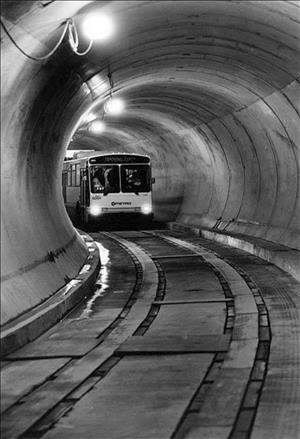

City capital projects tended to be modest during the 1970s and early 1980s, and focused on housing and maintenance bonds. Metro and King County undertook more ambitious projects such as the downtown bus tunnel and conservation of farmland. The 1985 Woodland Park Zoo Bonds set a new precedent when County taxpayers funded improvement of a City-owned facility.

City taxpayers expressed renewed confidence in the 1980s by approving bonds for a new Downtown Art Museum and public housing, but deep divisions over the pace and scale of development tended to discourage major public investment in the early 1990s.

It was all the more significant, therefore, when voters of three counties approved Sound Transit's multi-billion regional transportation plan in 1996, and Seattle voters approved nearly $200 million in 1998 to modernize the Seattle Public Library system. Only time will tell if today's economic optimism will sustain a new surge of public and private investments to benefit the citizens of the next century.

Licensing: This essay is licensed under a Creative Commons license that encourages reproduction with attribution. Credit should be given to both HistoryLink.org and to the author, and sources must be included with any reproduction. Click the icon for more info. Please note that this Creative Commons license applies to text only, and not to images. For more information regarding individual photos or images, please contact the source noted in the image credit.