This is a slideshow on the history of Seattle's University District, Part One: Gunther Chain to Bascule Bridge. Written and Curated by Paul Dorpat, with Chris Goodman.

Seattle's University District -- a Slideshow of its Early History (1890-1919)

- By Paul Dorpat

- Posted 1/01/2000

- HistoryLink.org Essay 7084

James Moore, Seattle'Â’s boom-years super-developer, platted the future University District in 1890. At the time it was not at all certain that the University of Washington campus would be relocated from downtown Seattle to the mile section of old growth forest bordering the east of his suburb of stumps.

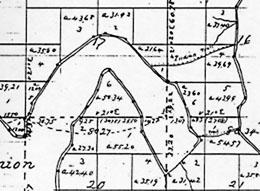

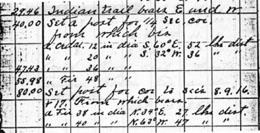

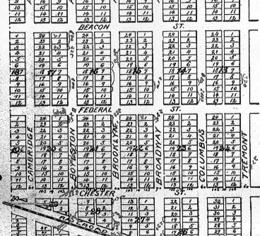

Federal surveyors first described and made detailed maps of the future University campus (section 16) and its future University District (section 17). The national land survey that began in Ohio in 1785 reached the north shore of Lake Union in the late summer of 1855.

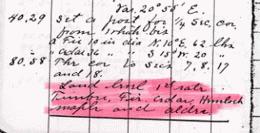

According to the surveyor general’'s field notes, the land along the future 45th Street was "“First rate [with] cedar, hemlock, maple and alder."” Two weeks earlier, on Sept 8, 1855, the surveyors worked their 66-foot Gunters chain along the future line of 15th Avenue NE – -- since 1895 the dividing line between "“town and gown”" or District and campus:

Here their record keeping was more detailed. At the intersection of 15th Avenue NE with 45th Street NE they described several fir trees with bases 10 feet around.

At 50 chains (3,300 feet) and 54 links (another 36 feet) south of the future 45th Street, the surveyors crossed an Indian trail. Here they momentarily left their line work between sections 16 and 17 and followed the path to the east. The trail connected two Indian camping sites, one on Portage Bay near the foot of present-day Brooklyn Avenue and the other on Union Bay near the present-day University of Washington power plant.

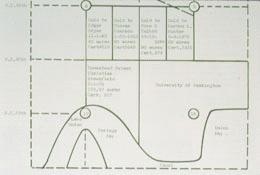

There are, it seems, no surviving photographs of what the University District’'s first settlers, Christian and Harriet Brownfield, called their "“Pioneer Farm."” The Missouri couple and their three children first settled section 17 in 1867. This map shows the site --– just west of section 16 (the future campus) and south of the future 45th Street to Portage Bay.

David Denny, one of Seattle’'s founders, visited the Brownfield farm in 1875 and found "“from 8 to 12 acres cleared … -- fenced in rail, picket and brush. It is in an oblong form. What land is cleared is fertile. Mr. Brownfield and son told me the best portion of the land lies back from the tides.”" Before its outlet was dammed in 1888, Lake Union had "“tides" ”-- the water level varied according to the season. The Brownfields raised livestock and grew produce that they sold in Seattle.

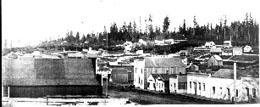

Harriet and her two daughters remained in Seattle (shown here in 1869), while Christian and their son Curtis cleared the first three acres and built a tongue-and-groove cabin. In the spring of 1869 the women joined the men. One year later the 1870 federal census noted "“one milk cow and a few chickens.”"

In 1886 Christian Brownfield and his son Curtis posed for a formal portrait. The ear trumpet that the older Brownfield wears like a necklace was his constant companion. Christian lost most of his hearing in a farming accident.

In 1872, Christian Brownfield and his son Curtis were hired to yoke two of their cattle to haul coal cars across the Montlake Isthmus. This portage between the two lakes was the shortest part of the difficult route chosen by California capitalists to move the coal of Coal Creek and Newcastle to the Seattle waterfront.

Curtis Brownfield also piloted the little Lake Union steamer Clara that pulled the coal scows from Montlake to the southern end of the lake where the cargo was dragged ashore for its last haul by a narrow gauge railway up the future route of Westlake Avenue to Pike Street...

and eventually to the Pike Street Coal Wharf. The Brownfields continued to do this work until 1878 when the company abandoned the line and wharf...

for a simpler route from the coal fields east of Lake Washington around the south end of the lake to a new and larger wharf and bunkers at the foot of King Street.

Four years later, in 1882, pioneer David Denny opened his Western Lumber Mill at the south end of Lake Union. This view looks north from Denny Hill over the mill to the lake'Â’s still forested distant north shore.

In order to supply his mill with the old-growth timber that still crowded the shores of both Lake Union and Lake Washington, David Denny soon returned to the Montlake Cut where he and other speculators contracted Chinese laborers to dig a log canal through the isthmus.

They finished a job that Harvey Pike started 20 years earlier. Pike traded his labor for helping to build the original University campus for title to the Montlake Isthmus. He soon platted it as Union City – a grand name for his hope that soon the natural wealth surrounding the big lake would reach the brokers and manufacturers of Seattle by way of his “"city."” In 1862, Pike even began digging a canal, but soon gave up. These “Now-&-Then views look down on Pike'’s “Union City,” aka Montlake, from Capitol Hill.

At the west end of Montlake Canal, logs could be sent down a flume (left of center), or lowered – ordinarily about nine feet -- to Portage Bay through locks (center). This ca. 1890 view looks from the canal towards the north end of Capitol Hill.

Until the ship canal replaced it in 1916, about 200 yards to the north, the Montlake log canal delivered thousands of raw logs to lumber mills on the shores of Lake Union.

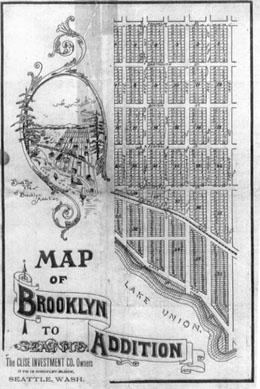

In 1875, Harriet and Christian Brownfield, the University District’'s first settlers, were granted one of Washington Territory’'s rare divorces “on the grounds of "incompatibility of tempers."” In the 1880s, Christian Brownfield sold most of his acres to speculators. After two failed tries by others to develop "“Pioneer Farm”" into a new north-end suburb called first Lakeside and then Kensington, James A Moore, in partnership with the Clise Investment Company, platted the Brooklyn Addition on December 19, 1890.

Separated from Seattle by Lake Union, the Brooklyn Addition was named to be analogous to Brooklyn, New York, which was “"over the water"” from Manhattan. On the Brooklyn addition map, University Way -- aka the Ave -- is named Columbus Street, Brooklyn is called Broadway, 12th Avenue is named for the addition, and 45th Street is called Franklin. Seattle annexed the north end including Fremont, Latona, Brooklyn, and Green Lake (but excluding Ballard) in 1891, soon after the filing of the Brooklyn Plat.

The mid-1960s aerial looking north over Portage Bay to the University District can be compared to the Brookyn Addition'Â’s 1890 cartoon birdseye.

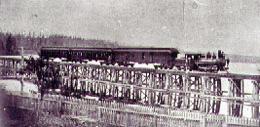

James MooreÂ’'s Brooklyn speculation was made accessible by the 1887 construction of the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railway from the Seattle waterfront to the north shore of Lake Union by way of Smith Cove and Interbay.

This view of the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern engine J. R. McDonald (named for the president of the line) on the north shore of Lake Union was probably photographed in the late 1880s and so before James Moore opened his Brooklyn Addition. The train poses on a pile trestle near the foot of Stone Way. Behind the train, the familiar ridge of Capitol Hill runs across the entire scene.

By fall 1887, the new line reached the north shore of Union Bay, and soon the enterprising Presbyterian minister William Beck and his artistic wife, Louisa, purchased the picturesque gorge through which the Green Lake outlet reached Union Bay. They called the park and their community Ravenna after an Italian town loved for both its culture and woods.

The eastern entrance to Ravenna Park shows on the far left beyond the few storefronts that make up the commercial center of the railstop Ravenna. In the distance, the main building of the Seattle Female College -- another of the Beck’'s enterprises – -- shows above the rooftop of their community.

The curve in the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railway tracks is repeated near Blakely Street in this contemporary (late 1990s) detail along the Burke Gilman Recreational Trail that replaced it.

The Seattle Female College at Ravenna Station opened in 1890, five years before the arrival of the University of Washington at University Station.

However, along with many other institutions, the school failed following the economic panic of 1893.

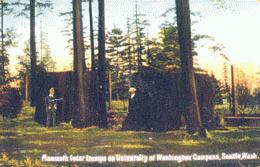

Ravenna ParkÂ’'s most sublime attractions were its big trees. Like Adam and Eve, the Becks had the privilege of naming them. They gave one ancient fir the name Adam. They named another Paderewsky after the Polish pianist who was a friend of Mrs. Beck.

They puckishly titled two giants that crowded one another Mark Matthew and Hi Gill after the local Presbyterian pastor and the Seattle mayor, who were usually fighting.

They named the tallest fir -- a spectacular tree that rose nearly 400 feet to about two-thirds the height of the Space Needle -- Robert E. Lee.

And what Mrs. Beck humorously referred to as the "“big stick,"” a giant with the largest girth, she named Roosevelt for the president who visited the park and whispered his sublime approval.

Here, near the southeast corner of Lake Union, David Denny poses at the forward end of his street railway to Ravenna, during times that were still good.

The Denny line bridged the narrow entrance to Portage Bay at Latona. With its July 1, 1891, dedication, the Latona Bridge surpassed the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railway as the popular gateway to the newly annexed additions of Latona and Brooklyn. By then David DennyÂ’'s street railway was but one of the several trolley lines that radiated from the central city into the new suburbs of Leschi, Madison Park, Ballard, Fremont, Columbia City, and Brooklyn.

The rough landscape at the north end of Capitol hill is revealed in this 1893 view of the Latona Bridge from the fledgling town of Latona. The structure on the right sets near what is now (2004) the entrance to IvarÂ’'s Salmon House. All surface traffic to Brooklyn had to come through Latona. The Latona business district, its post office, and its primary school predate those of Brooklyn.

In the early 1960s, Interstate 5 separated the University District from Wallingford and left Latona divided between them. The Freeway Bridge lies exactly in line with the former Latona Bridge.

Latona'Â’s second wood frame school building (left) was built beside the first in 1907. A third building made of brick (right) was added in 1917. Enrollment reached its all time high in 1921 when 17 teachers somehow managed to instruct 639 students.

Until the 1903 opening of University Heights School, the children of Brooklyn attended Latona Primary. The new school was a victory for the University Community Club and especially for its first president, U.W. Professor B. W. Brintnall. Brintnall led the club through the rare process of caring more for the community'Â’s children than for its streets, sidewalks, and stray cows.

North and south wings were soon added to the schoolÂ’'s original core, and by the early 1920s the student body at University Heights was one of the city'Â’s largest. Also by then, the commercial structures shown on the left of this ca. 1910 postcard were removed in order to extend the playfield of the school.

In his 1894 map of the “real roads” of Seattle, the cartographer McKee shows a greater interest in Latona – -- which is listed --– than in Brooklyn, which he does not bother to name. The route of the trolley line to Ravenna is marked on Columbia Avenue (now University Way). One block west, Broadway Avenue (now Brooklyn Avenue) is also included as “"real."”

The 1892 move of streetcars one block east, from Broadway (Brooklyn Avenue) to Columbia, did not mean that Columbia quickly became the new community’'s "“Main Street."” Brooklyn Avenue remained the busier commercial street at the turn-of-the-century, although ultimately University Way took away most of its businesses and added many more new ones. "The “Ave"” had the trolley.

With the 1895 arrival of the University of Washington, the common name for the University District became "“University Station"” rather than developer James Moore’'s New York analogy: Brooklyn. "University Station" had a double meaning.

First, in 1895, the university built the waiting house at the northeast corner of the Ave and 42nd Street, seen here, in part, (far left) beside the Varsity Inn. Students huddled in the shed to keep warm while waiting for the Third Street and Suburban RR Co. cars. In 1895, the street trolley left for town roughly every half-hour. Beside it, the Varsity Inn was more than a popular student retreat. A combination store, hotel, and restaurant, the Varsity Inn featured an ambitious multi-course menu.

A second meaning for “"station"” was added in 1902 when the post office was moved from Latona (under protest) to Brooklyn. Stationed first at the northwest corner of 42nd Street and across the Ave from the trolley shed, it was later moved across the street into the new brick LaPaz building built just behind and to the east of the old Varsity Inn as seen here. The hard-to-decipher sign stuck to the top of the snow pile (during 1916 big snow) seems to read “"Cold refuge, Post Office."”

When the student body moved to its new campus in 1895, the Administration Building housed all the schoolÂ’'s functions -- offices, classrooms, library, laboratories, and auditorium.

Denny HallÂ’'s belltower offered a sweeping prospect of the community. This mid-1890s view looks over Brooklyn toward the Latona Bridge. On the left is the north end of Capitol Hill. Beyond the bridge, the Wallingford peninsula (future site of Gas Works Park) projects into Lake Union. Farther still, Queen Anne Hill marks the horizon.

Later, the Administration Building was named for Arthur Denny, who gave the first land for the Territorial University at its original location on Denny Knoll, and who in 1860 politically engineered SeattleÂ’'s pioneer acquisition of the school through the territorial legislature.

Very few photographs of the University District in its Brooklyn years survive. This rare early-century glimpse of the Latona Bridge views it over what in the foreground may be the intersection of Brooklyn Avenue and 43rd Street. The low land in the middle ground is the future route of Roosevelt and 11th avenues.

Brooklyn is also revealed in Asahel Curtis'sÂ’ 1903 panorama which looks across Portage Bay from the north end of Capitol Hill. The sparsely settled blocks of the small community are bordered on the east by the still largely wild University of Washington campus.

The last blocks of the "“Lower Ave,"” – -- still called Columbus Street – -- were photographed by a representative of the famous Olmsted Architectural Firm visiting Seattle to survey the city for the firm’'s city-wide parks and boulevards plan. This view looks south from near 40th Street. Capitol Hill is on the horizon above Portage Bay.

In 1905, the approximate date of this view on University Way north of 43rd Street, Murphy'Â’s Meat Market wagon and its driver Hurd Porter pose for an unknown photographer. The Ave was first paved in 1908, in time for the summer-long Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition held on the University of Washington campus. Before A-Y-P the Ave north of 43rd Street was still largely residential.

Since 1925, when it moved from campus to the Ave, the UW Book Store has been associated most with this block south of 45th street.

On September 28, 1906, 16 years after platting the Brooklyn Addition, James Moore formally opened his University Park Addition, across 45th Street from the UW campus. Moore gave to his grand boulevard, 17th Avenue, which led to the UniversityÂ’'s north entrance, land that he took from other avenues like 18th and 19th, which are today too narrow and congested. Soon many of the schoolÂ’'s sororities and fraternities moved from their first homes on Brooklyn Avenue and University Way to grander quarters beside the incongruously narrow avenues of MooreÂ’'s new addition.

The best view of the University Park Addition and its featured boulevard was had from the UniversityÂ’'s water tower built just south of 45th Street.

The watertower was neighbor to the school'Â’s observatory. This view of both was photographed from the bell tower of Denny Hall.

The cover of The Interlaken is evidence that the future University District was still called Brooklyn in 1907, when the University of Washington had been its neighbor for 12 years. The cover of the tabloid promotes the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. After the A-Y-PÂ’'s summer-long run on the university campus, the district was more frequently given the name of its academic neighbor.

The north end of 14th Avenue (University Way) was landscaped in 1907 with the dedication of Cowen Park. The English immigrant Charles Cowen purchased the land in 1906 and gave it to the Seattle Park Department. This view looks north of the Ave towards the park'Â’s rustic gate.

In 1908, University Way just south of 45th Street was still largely residential. The commercial center of the Ave was still two long blocks south at “"University Station."”

After the 1895 opening of the University of WashingtonÂ’'s new campus, the largest influence on the growth of the district (and of Seattle) was the prestige and community-wide productions that accompanied SeattleÂ’'s first world's fair: the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, held on campus through the summer of 1909.

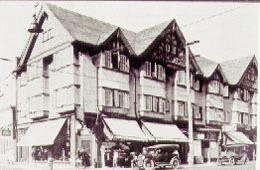

The Tudor College Inn at the northeast corner of University Way and 40th Street is part of the legacy left by the enthusiasm surrounding the 1909 A-Y-P. Like the summer-long fair, the College Inn opened on June 1, 1909.

The recent photo was taken in 2001.

Graced with a fine cornice, bay windows, and store interiors revealed to the street through large windows, the elegant Lisbon Apartments was another of the structures raised on the Ave in time for the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition.

Following World War II, the Lisbon was stripped of its bay windows and covered with a modern aggregate siding. The remodeled Lisbon was then renamed for its new owner, University District real-estate agent Don Kennedy. Many more of the AveÂ’'s commercial structures have lost their traditional ornaments to minimal modern facades.

This 1910 panorama from Queen Anne hill shows the University District, University campus, and much else in the first year following the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. The view looks over the Gas Works peninsula to the north end of Capitol Hill on the right, the University district and campus beyond the timber trestle of the Latona Bridge -- which seems to close the opening to Portage Bay. Portions of Laurelhurst, Lake Washington, and Kirkland are also visible beyond the campus. The University'Â’s Denny Hall, Science Hall (Parrington), and (old) Meany Auditorium are all visible directly above the Gas Works. The scaffolding of the Federal Building of the fair is also apparent to the right of the large boxish Meany Auditorium.

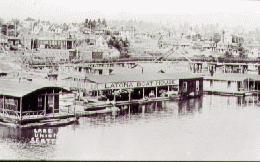

In 1910 the Latona Boat House was one of the popular providers of recreational vessels -- mostly canoes -- used on the lake. The pipeline above the boathouse supplied the north end with Cedar River water. Before it was tunneled beneath Portage Bay, the pipeline crossed the lake on its own narrow timber trestle parallel to the Latona Bridge. This 1910 view was photographed from the Latona Bridge. On the far right, Parrington Hall interrupts the horizon line of campus trees.

In its last year of service, the Latona Bridge consisted of two spans side-by-side, one opened by lift and used exclusively by trolleys and the other a swing bridge for autos and wagons.

Soon after the bridge was closed in 1919 with the opening of the University Bridge, the Latona Business District withered away. Sylvian Paysee, the communityÂ’'s principal pioneer merchant, led the Latona move to University Way, reopening his hardware store in the Adelaide Building at 50th Street.

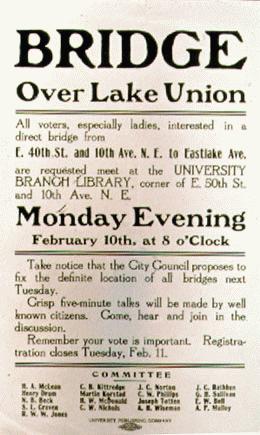

This broadside encouraging community input on the siting of the first University Bridge was published early in the campaign, ca. 1914.

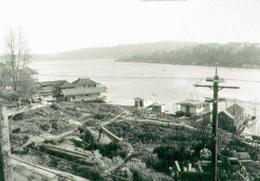

The view of Portage Bay looks over the point where the city planned the University Bridge to reach Lake UnionÂ’'s north shore. A Department of Public Works photographer made the photograph on March 18, 1915.

For the July 1, 1919, dedication of the University Bridge, the seats of two patriotically adorned streetcars were reserved for University District leaders and local politicians. Seattle Mayor Ole Hanson was at the controls of the first car that carried the policemen'Â’s band.

The cars headed first north across the bridge and then back again for speeches and music at the south end of the new bridge.

Licensing: This essay is licensed under a Creative Commons license that encourages reproduction with attribution. Credit should be given to both HistoryLink.org and to the author, and sources must be included with any reproduction. Click the icon for more info. Please note that this Creative Commons license applies to text only, and not to images. For more information regarding individual photos or images, please contact the source noted in the image credit.