Community Scrapbook: East Green Lake, 1888-1909

- By Paul Dorpat

- Posted 5/12/2006

- HistoryLink.org Essay 7762

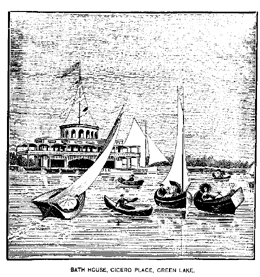

Perhaps the first illustration that pretended to show off the beauties of Green Lake were included in an 1888 Special Edition on Seattle published by the Portland, Oregon, newspaper, the Oregonian. The two etchings of Green Lake were entirely fanciful. In 1888, there was no bathhouse with a grand portico, no fleet of recreational sailboats, no Cicero place. When the future "father of Green Lake," William Wood first approached the lake in 1888, he discovered that its was "still skirted at most points by an impenetrable jungle ... It seemed to me that no living creature had ever gone through there before unless perhaps a bear, it was such a tangle of briers, berry bushes, thick timber and fallen logs in every shape." However, in 1888 Wood had ambitious plans and proposals for Green Lake, including one for a park. Most likely it was his well-advertised ambitions that informed this fanciful drawing. When the electric trolley from Fremont to Green Lake was completed around the east and north shores of the lake in 1890, it first terminated at a 10-acre amusement park developed by Wood near the present site of the Bathhouse. Wood noted that the hill slopes around Green Lake were "so gentle that the lake itself is free from squalls or winds that would be dangerous for amateur boating."

Andrew L. Parker lists himself twice in the 1892-93 Seattle City Directory. Once as Reverend Parker, and again as the proprietor of the Green Lake Sawmill. For his Green Lake home Parker chose the arcane but mellifluous name "Parcuvia." Parker’s mill had a capacity of about 20,000 feet a day and many of the homes built nearby during Green Lake’s first boom years in the early 1890s were constructed from his product. Predictably, the effects of his lumber mill on the gentle hills surrounding Green Lake were neither spiritual nor picturesque. Parker opened his mill in 1890 near the contemporary site of the recreation and community center at the northeast corner of the lake. Here, the Green Lake Mill is seen from a prospect that looks north from the east shore of the lake. Parker’s timing took advantage of the completion in the Spring of 1890 of the Green Lake Electric Trolley between Fremont and Green Lake. The trolley was routed along the east shore of the lake and ran as far as a small amusement park developed at the northwest corner of the Lake. By far the most important stop was at Woodland Station, or East Green Lake near the mill, and for at least two years the line’s most important rider was Parker’s lumber.

In 1887, William and Emma (Wallingford) Wood purchased from John Siegfried -- "Green Lake John" as he was called -- the land and cabins Siegfried first settled and built 18 years earlier at the northeast corner of Green Lake. William Wood remembered that when he first saw Green Lake in 1888 he was "at once impressed with its beauties and possibilities.” This view looks north across NE 72nd Street to the Wood home between Green Lake Drive N and Woodlawn Avenue N. Not the family but the family cow appears at the center. We may use the cow as a pointer to one of Green Lake John’s surviving log cabins. It appears just above the bovine rump. By all accounts William Wood was the most important character in the early development of Green Lake. He bought hundreds of acres of land bordering the lake for development, was president of the company that completed the electric trolley to Green Lake in 1890, and also that year paid dearly to have the first telephone strung to his new home. Wood and his neighbors voted to be annexed to Seattle in 1890. In six years more, Wood became easily Green Lake’s most distinguished citizen when he was appointed Mayor of Seattle.

Here is a "stump-pullers" view (note the man in the lower right-hand corner) that looks west over Green Lake to Phinney Ridge. The man and boy in the foreground stand very near -- perhaps on -- today's I-5 Freeway. The photograph is signed "Conn." "Professor" George E. Conn probably took his series of north-end photographs in the late 1890s. From 1897 to 1899, Conn was the principal at Green Lake School -- hence the "Professor" moniker -- and his revealing handful of Green Lake views probably date from those years. And what is revealed? Most obviously land cleared but hardly developed. Conn recorded this view after Andrew Parker had moved his Green Lake Mill on to another location where yet unharvested old growth Cedars and Douglas Firs awaited his blades. Parker did his milling here in the early 1890s. The trees left standing in this scene are scraggly unwanteds. Sited at the northeast corner of Green Lake, the Parker Mill would show in this scene if still around. The Conn photograph also includes two windmills. One is half-hidden behind the tree on the right. The other stands on the left near the shoreline. This last is a comely three-tiered pagoda-like windmill.

On November 26, 1903, The Green Lake News printed its first anniversary issue. It includes a three-negative panorama of Green Lake photographed that year by the local photographer Asahel Curtis. About one-half of the Curtis work is printed here. The view looks west over the East Green Lake neighborhood, to Green Lake, Phinney Ridge, and the Olympic Mountains on the horizon. If only by evidence of this scene, the enthusiasm of The Green Lake News was warranted. The growth around Green Lake, especially East Green Lake, had been phenomenal. John Martin, a resident writing for the special issue, noted that three years earlier when he moved to Green Lake answering a call "for freedom from the noisy traffic of the city ... not more than 500 people surrounded it. Now there are nearly 10,000." Martin was not complaining. In 1900 he had purchased 20 previously quiet Green Lake lots. Another estimate printed in the anniversary issue put the population of the Green Lake suburb at 8,000 people, with "about 6,200 of these on the east side of the Lake." The residents were connected to the city’s Cedar River water, and they were also powered electrically. W. D. Wood, the "Father of Green Lake," recalled for the News how when he and Guy Phinney first developed East Green Lake and Woodland Park, respectively, in 1890, Phinney had told him that "soon Green Lake would be ringed by electric lights." Wood noted "I thought he was a dreamer then. As I see electric lights everywhere at the lake I often think of this."

One part of the general fad for sending and receiving penny postcards that overtook Western culture in the early twentieth century was the depiction of neighborhood business blocks. These were evidences of local pride sent to distant friends and relatives. This view of East Green Lake NE 72nd Street looking east from Green Lake Drive N is a good example -- especially for a Western American community. All of the structures here are constructed of wood with the exception of the single story brick bank that sits just left of center at the southeast corner of 72nd and Woodlawn Avenue N. The intersection that was the heart of the East Green Lake business district. In 1911, a speculative date for this postcard George Lear’s Green Lake State Bank was one of only three north-end banks. The others were in Ballard and the University District. Before the University of Washington hosted the summer-long Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in 1909, the Green Lake business district considered itself easily the equal of its neighbor, the University District. Included among the other businesses revealed on the south side of 72nd Street are the North End Bath House, the two-story frame structure just beyond the bank, and in the immediate block right-of-center, storefront clapboards featuring the Central Market and the Model Grocery, names conventional like the postcard subject itself. One last "required" touch, albeit dim, may be noted. Left of center and two blocks distant is the steeple-topped church of the Green Way Baptists at the southeast corner of 72nd Street and 5th Avenue NE.

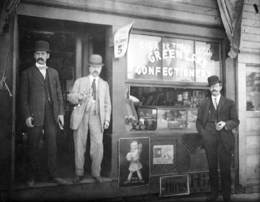

Perhaps signaling the risk of starting up a small business, the Green Lake Confectionery does not appear in the 1908, 1909, or 1910 Business Directories, although this photograph was almost certainly recorded in 1909. It is one of several views included in a collection of commercial portraits recorded that year. Usually the photographer would have been paid a fee by the store owner to include his or her business as part of a neighborhood photographic survey or some advertised special. Whatever, the trio standing here did not apparently gain much fortune from this candy store nor fame from this portrait. We may assume, however, that the Green Lake Confectionery was at least for a few months one of sweeter parts of the East Green Lake business district.

Licensing: This essay is licensed under a Creative Commons license that encourages reproduction with attribution. Credit should be given to both HistoryLink.org and to the author, and sources must be included with any reproduction. Click the icon for more info. Please note that this Creative Commons license applies to text only, and not to images. For more information regarding individual photos or images, please contact the source noted in the image credit.