The Seattle Public Utilities water system provides direct water service to around 630,000 people in and just outside the City of Seattle and sells water wholesale to cities and water districts serving another 720,000 people. Seattle's publicly owned water system began in 1890 with the purchase of several private water companies. Creation of a gravity supply system from the Cedar River beginning in 1901 gave Seattle enough water to accommodate its own growth and supply an ever-increasing number of other jurisdictions. Inauguration of the South Fork Tolt River supply in the 1960s added a second source, ensuring adequate supplies well into the twenty-first century. As the system grew and water quality requirements increased, water treatment evolved from manual application of chlorine at intakes to the current sophisticated Tolt and Cedar River treatment facilities. This slideshow history of the Seattle water system was written and curated by Kit Oldham.

Seattle Water System -- A Slideshow

- By Kit Oldham

- Posted 4/14/2010

- HistoryLink.org Essay 9386

Henry Yesler and other early settlers built Seattle's first water systems using open wooden flumes, and later pipes consisting of hand-bored logs, to carry water from springs in the slopes above downtown to the small settlement on Elliott Bay. In the 1880s private companies developed more extensive systems, pumping water from Lake Washington and Lake Union to small reservoirs and tanks that served the growing city. By then, Mayor Robert Moran and others were urging construction of a gravity supply system using the abundant water of the Cedar River, whose watershed stretches into the Cascade Mountains east and south of Seattle.

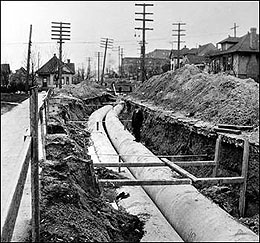

Shortly after the Great Fire of 1889, during which private systems failed to supply adequate water for firefighting, Seattleites voted overwhelmingly in favor of building the Cedar River system. Seattle's Water Department came into being in 1890, when the city acquired the Spring Hill Water Company, which pumped water from Lake Washington. It took a Supreme Court decision and another, much closer vote in favor of a publicly owned system before construction began on a pipeline from the Cedar River at Landsburg, where an intake dam was built, to the city. In 1901, the first Cedar River water flowed into new reservoirs at Volunteer and Lincoln (now Cal Anderson) parks.

With Seattle growing rapidly, and tens of thousands of visitors coming to town for the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, a larger second Cedar River pipeline nearly tripled the system's delivery capacity in 1909. Two years later two "Green Lake" reservoirs (now Maple Leaf and Roosevelt) and twin Beacon Hill reservoirs opened.

The abundant supply from the two Cedar River pipelines supported Seattle's own continuing growth through immigration and annexation and allowed the city to supply water to an increasing number of water systems outside its limits. In the early decades of the twentieth century, huge quantities of "surplus" water were also used to sluice down Denny Hill and large chunks of Beacon Hill in massive regrading projects.

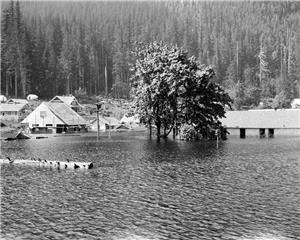

In the 1910s, construction of the Masonry Dam in the Cedar River gorge increased the storage capacity of Cedar (now Chester Morse) Lake, but the project was plagued from the start by seepage through the morainal fill on the north side of the gorge. Water seeping through the moraine raised Rattlesnake Lake and slowly flooded the town of Moncton; water also reached Boxley Creek, where heavy rains and a washout near the dam triggered the "Boxley Burst," a catastrophic flood that destroyed the town of Edgewick.

Over the years, the City bought up land in the Cedar River watershed in order to protect water quality by eliminating residence and most human activity in the watershed. However, the City could not afford timbered land, so logging was allowed to continue. A 1924 report by University of Washington forestry school dean Hugo Winkenwerder and graduate student Allen E. Thompson found that the private logging operations and the fires that followed in their wake were ruining the watershed, and recommended a program of reforestation and sustained yield forest management. Thompson was hired as city forester to implement the program and supervised watershed forests for the next 40 years.

The third Cedar River pipeline began delivering water in 1923. Over the next several years Lake Youngs (named for Superintendent L. B. Youngs, who headed the Water Department for 28 years until his death in 1923) was developed as a storage reservoir with a control works at Molasses Creek at the lake's outflow, where automatic chlorinators replaced early manually operated machines that had been used at the Landsburg intake.

During the 1930s, City plans to construct a City-owned water main north of the existing city limits at 85th Street were opposed by a private company that hoped to develop a water supply from the Tolt River to serve that area. Voters in the area preferred the city plan and the private company dissolved. Within a few years, Seattle applied for and received water rights on the North and South Forks of the Tolt River as a potential addition to the Cedar River supply.

In 1944, a report by the Cedar River Watershed Commission called for improvements in water quality practices and the U.S. Public Health Service established new national potable water standards and tests to enforce those standards. In response, the City Council placed full responsiblity for water quality (previously shared with the Health Department) on the Water Department, created a sanitary division and testing laboratory within the department, and required chlorination at city reservoirs (in addition to the control works).

The fourth Cedar River Pipeline, providing a direct supply to the Bow Lake Reservoir that served Seattle Tacoma International Airport and vicinity, was completed in 1954. Three years later, the East Side Water Supply line was finished, allowing the Water Department to supply Mercer Island and nearby areas on the east side of Lake Washington for the first time.

Construction began in 1959 on the first stage of the Tolt River Water Supply Project, including the South Fork Dam and storage reservoir, the Lake Forest Park Reservoir, and 30 miles of pipeline. The first Tolt water was delivered in late 1962, after completion of the pipeline and Lake Forest Park Reservoir. The South Fork Dam was dedicated in 1964. Soon after, Seattle's water service area expanded significantly with the addition of Bellevue and other large districts on the east side.

Through the mid-1980s, water consumption rose as the population served grew, reaching an all time annual high in 1984. Consumption leveled off for the rest of the decade, with nearly comparable figures in 1985, 1989, and 1990. Despite continuing population growth, consumption then fell, with a sharp drop in the drought year of 1992, as (temporary) use restrictions, rate increases, and education encouraged conservation by users and as system improvements reduced the amount of non-revenue water use. After slight increases in the late 1990s, additional conservation measures beginning in 2000 brought significant further declines in consumption, even as population kept growing.

Following a 1978 inspection, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers concluded that the Masonry Dam on the Cedar River was unsafe due to continued seepage through the morainal sands and gravel of the right abutment. A major renovation, completed in 1987, brought the dam up to standards. A new Emergency Spillway that can handle a probable maximum flood without risking a breach of the abutment was constructed, and other components of dam were rehabilitated.

Beginning with View Ridge Reservoir, which opened in 1978, all new reservoirs were built covered (generally underground) to enhance water quality, reduce water loss, and improve security. In 1994, Magnolia Reservoir became the first existing reservoir to be replaced by a new underground facility with a park on the open space above. Lincoln Reservoir in what soon became Cal Anderson Park followed in 2004, new underground Beacon Hill and Myrtle reservoirs were completed in 2009, and undergrounding the Maple Leaf and West Seattle reservoirs is scheduled for completion by 2012.

During the 1990s, the city began developing the Cedar River Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) in anticipation that Puget Sound salmon would be listed under the Endangered Species Act (the listing occurred in 1999). The HCP, a 50-year plan addressing declines in salmon and other species through improved fish passage, watershed management, and stream-flow management, was approved in 2000. A fish ladder, gate, bypass, and rock drop were completed at Landsburg in 2003, allowing chinook, coho, and steelhead to spawn above the dam for the first time in more than a century.

The Cedar River Watershed Education Center, funded by the City and the Friends of the Cedar River Watershed, a private nonprofit group, opened in 2001 as a cultural and environmental education center providing information on the watershed's forests, wildlife, water supply, and 9,400-year history of human activity. The center consists of five sustainably designed buildings linked by walkways, and features art, including water drums played by dripping water, and exhibits, documents, and artifacts detailing the area's natural and human history.

As federal and state water quality requirements grew increasingly stringent, water treatment facilities became ever more comprehensive and sophisticated. The current treatment facilities for the Tolt and Cedar systems (completed in 2000 and 2004 respectively) provide chlorination, ozonation, corrosion control, fluoridation, and screening, as well as filtration (of the Tolt supply) or ultraviolet light treatment (of the Cedar supply).

Licensing: This essay is licensed under a Creative Commons license that encourages reproduction with attribution. Credit should be given to both HistoryLink.org and to the author, and sources must be included with any reproduction. Click the icon for more info. Please note that this Creative Commons license applies to text only, and not to images. For more information regarding individual photos or images, please contact the source noted in the image credit.