This is Part 1 of a three-part slideshow photo essay on the history of the Seattle Aquarium and its neighborhood beginning in 1841 through the present day. Part 1 takes the story from the early dates of settlement along the Seattle waterfront to the Great Seattle Fire of 1899. Curated by Paul Dorpat. Edited by Walt Crowley. Presented by the Seattle Aquarium Society.

Seattle Aquarium Slideshow, Part 1: From Settlement to Cinders, 1841-1899

- By Paul Dorpat

- Posted 1/22/2005

- HistoryLink.org Essay 7052

The award-winning Seattle Aquarium opened on May 20, 1977. It occupies Piers 59, 60, and 61 between Pike and Union Streets on the central waterfront. Now the subject of new redevelopment plans, the present Aquarium is but the latest improvement in a long and rich history of maritime and recreational activity dating back nearly to Seattle's birth in the 1850s.

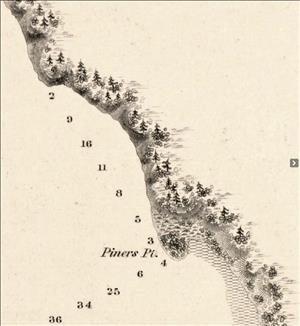

In 1841, U.S. Navy Lt. Charles Wilkes conducted the first detailed survey of Elliott Bay, which he named for a member of his crew. While the bay offered excellent anchorage, he observed that much of its eastern shoreline was guarded by a notched escarpment of steep bluffs. He dubbed the only large level area Piner's Point (shown in this detail from Wilkes's chart), although it became an island at high tide.

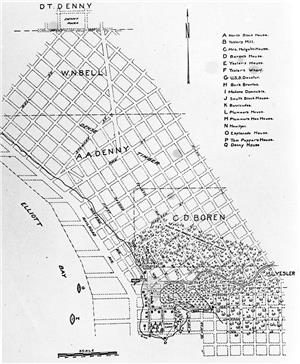

It was there that Seattle's first white settlers alit in the spring of 1852. This 1910 map superimposes Seattle's later street grid over a map drawn in 1856. It shows the village's early structures clustered on or just north of Piner's Point, including Henry Yesler's wharf at the foot of his namesake street, in what is now Pioneer Square. The marsh to the east and tideflats to the south were not filled in until the early 1900s.

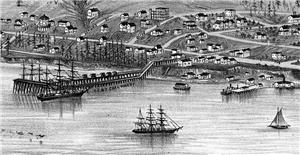

Nearly all of Seattle's future waterfront remains untouched in this detail from a rare view taken in 1869 by Victoria, B.C., photographer George Robinson. Note the sidewheeler pulling away from Yesler's wharf, and the steep bluffs lining the shore to the north.

Zooming in even tighter on Robinson's photo, we can see a pair of buildings hugging the shore and a low pier crossing the exposed beach. They stand directly below Arthur and Mary Denny's house, which puts them roughly at the intersection of today's Western Avenue and Union Street. These structures very likely constitute Seattle's first shoreline development north of Yesler in what would become the city's central waterfront.

By the mid-1870s, Seattle had spread north and east from its original foothold on Piner's Point. This detail from an 1879 U.S. Coast Guard Survey shows the "S.C.&T. Cos. Wharf" extending out from the base of Pike Street. This facility was built around 1872 by the Seattle Coal & Transportation Company to load colliers and fuel steamships with coal mined east of Lake Washington, and laboriously hauled to Seattle by barge and narrow-gauge railway.

For much of the late 1800s, coal -- not timber or salmon -- was Seattle's most important export. This detail from an 1876 photograph shows the coal pier, bunker, and narrow-gauge trestle. The whole affair collapsed into Elliott Bay a year later and it was not rebuilt. The lower photograph shows the stubs of the abandoned pier and trestle a few years after the accident.

Shortly before the coal pier went to Casey's Locker in 1877, Capt. William Jensen opened Seattle's first commercial bathing beach between Pike and Union Streets, not far from today's Aquarium. He rented towels and changing rooms to swimmers willing to brave Elliott Bay's frigid (and none-too-clean) waters. One oldtimer later reported that "the long-skirted bathing suits were a sight to see." Jensen's bath houses show up in this detail from an 1878 "bird's eye" map (along with the defunct coal dock), but both had already vanished by then.

Coal loading shifted south to the King Street area in 1879, thanks to the first line of the Seattle & Walla Walla Railroad. Although it never got close to the second city in its name, the railroad made money hauling coal from Renton to Seattle's coal docks. It crossed the Duwamish mudflats and headed north of Yesler via a curving trestle, dubbed the "Ram's Horn," shown in the detail from an 1884 bird's eye drawing.

The Northern Pacific Railroad magnate Henry Villard bought the Seattle & Walla Walla in 1880. The firm renamed the line the Columbia and Puget Sound and pushed its waterfront trestle north to Pike Street.

In 1887, work began on a second trestle for the new, locally owned Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railroad, located west of the C&SP right-of-way. (Much of the road's northern route survives today as the Burke-Gilman Trail, named for the railroad's two prime movers, Judge Thomas Burke and Daniel Gilman.) In this 1888 view from Seneca Street, the new trestle angles outward and passes between pier sheds belonging to the Columbia Canning Company, which succeeded Leary's furniture mill at the foot of Pike Street.

This 1888 view of the twin railroad trestles shows how they effectively blockaded the shoreline from the bay. The barrel-roofed structure where the two lines nearly meet housed the Allman & Philips Foundry near the foot of Union Street.

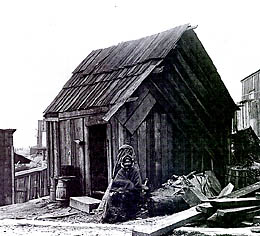

Native Americans, transients and squatters gradually erected a community of shacks and tents along the neglected shore. One of this area's most famous residents was Princess Angeline, or Kikisoblu, the daughter of Chief Seattle and his first wife. She lived just below Pike Street. A few, more sentimental settlers tended to her needs and even rebuilt the shack she occupied until her death in 1896.

Such shacks, along with sturdier wooden piers, trestles, and wharves, made good kindling for the "Great Fire" of June 6, 1889. The conflagration began with a cabinetmaker's overheated glue pot at 1st Avenue and Madison Street and raced simultaneously south to consume Pioneer Square and north along the waterfront. A bucket brigade finally stopped the flames' advance just short of Union Street, sparing downtown Seattle's few northern piers. The ruins along the main waterfront are still smoking in this view days after the blaze, but a pile driver has already begun reconstruction.

The railroad trestles were quickly rebuilt, as shown in this view from summer 1889. The pictured structures stand on the 1888 wharf of Schwabacher & Co., roughly where Pier 58 stands today, and barely escaped the Great Fire. The gaps between the two railroad trestles would soon be planked in to create "Railroad Avenue" and then Alaskan Way, as later views will show.

Continued in Part 2.

Licensing: This essay is licensed under a Creative Commons license that encourages reproduction with attribution. Credit should be given to both HistoryLink.org and to the author, and sources must be included with any reproduction. Click the icon for more info. Please note that this Creative Commons license applies to text only, and not to images. For more information regarding individual photos or images, please contact the source noted in the image credit.