This is Part 3 of a three-part slideshow photo essay on the history of the Seattle Aquarium and its neighborhood beginning in 1841 through the present day. Part 3 continues the story from the beginning of World War II (1941) to the present. Curated by Paul Dorpat. Edited by Walt Crowley. Presented by the Seattle Aquarium Society.

Seattle Aquarium Slideshow, Part 3: From World War Shipping to a World-Class Aquarium, 1941-present

- Posted 1/22/2005

- HistoryLink.org Essay 7165

To better coordinate shipping during World War II, the Federal Government decreed a new numbering system for Seattle's piers, which remains in use today. Wartime censors discouraged photographs of waterfront activities, so virtually no images are available of the harbor between December 7, 1941, the day the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, and August 14, 1945, when the war ended.

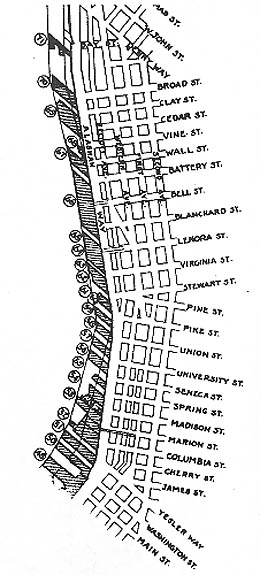

The Port of Seattle drew up elaborate plans for redeveloping the waterfront after World War II ended, but nothing much happened, as illustrated by this early 1950s postcard of a small trawler moored at Pier 61. Port officials and experts warned that larger ships and new methods had made the central waterfront's old piers hopelessly outmoded.

The first major post-war waterfront improvement (although some would debate the term) was construction of the Alaskan Street Viaduct, which diverted Highway 99 traffic off of downtown streets. This view of the upper deck (next to the old Armory) was taken shortly before its dedication in April 1953. The Battery Street Tunnel (originally dubbed "Seafair Lane") opened in 1954 and the final link to Spokane Street was completed five years later.

Pollution has not yet discolored the Viaduct in this 1955 aerial view. Note that the old Schwabacher shed on Pier 58 has been demolished and replaced with two finger piers to serve pleasure boaters. Nobody much cared to use it, but it did provide moorage to a floating hotel during the 1962 World's Fair.

Pier 58 was demolished a year before this 1968 photograph was taken. Note the original Seafirst Building (1001 Fourth Ave.) rising on the right. But for it and the broad white facade of the Washington Building (built in 1959, now Puget Sound Plaza), Seattle's central downtown skyline and waterfront had changed remarkably little since 1930. Development would soon accelerate as containerization shifted most shipping south of downtown, and planners began to eye the waterfront for new recreational, commercial, and residential uses. One of the most obvious needs was a decent public aquarium.

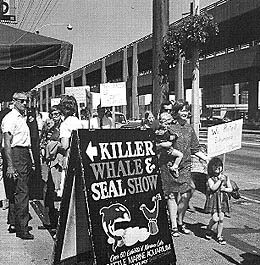

Unless one counts Ivar Haglund's old collection of fish tanks at Pier 54 and the Port of Seattle's "frozen fish museum," Seattle did not have an aquarium worthy of the name until the early 1960s, when home-heating-oil magnate Ted Griffin established his Seattle Marine Aquarium on the end of Pier 56. His capture and display of Killer Whales, beginning with the famous Namu in 1965, drew both visitors and protesters. A later captive, Kandu, and his would-be liberators are shown here in the early 1970s, not long before the federal government banned the capture of wild Orca.

In 1968, King County and Seattle voters approved more than $300 million in Forward Thrust bonds, including funds for a new Waterfront Park and public aquarium. In 1974, the City of Seattle began building the park in the gap between Piers 57 and 59.

Architect Al Bumgardner's design went through many changes prior to construction, but the end product succeeds in offering visitors both dramatic marine views and quiet waterfront retreats.

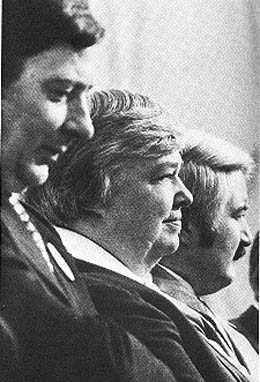

Locating and designing the new aquarium proved much harder. UW marine biologist (and future governor) Dixy Lee Ray wanted it put far north of downtown, at Golden Gardens at the mouth of Shilshole Bay, while Mayor Wes Uhlman championed a downtown location to promote tourism. He won that battle in 1972, but she beat him four years later for the Democratic Party's gubernatorial nomination. They are pictured here in 1974 (to the right of John Spellman) sitting as close to each other as they probably ever got.

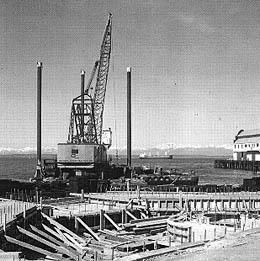

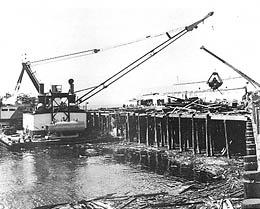

After much debate and more flipflopping than a beached flounder, the Seattle City Council agreed to locate the new Aquarium at Piers 60 and 61. The following year, they expanded it into Pier 59. By then, hyperinflation was fast eroding the project's $5 million budget, which had already been cut in half. In this view, demolition of Piers 60 and 61 has just begun.

By the time construction began in 1975, inflation had seriously shrunk the buying power of the Forward Thrust bonds. This forced architects Fred Bassetti and Skip Norton and exhibit designer/Aquarium director Doug Kemper to innovate cost-saving approaches that would not compromise the facility's educational and recreational missions.

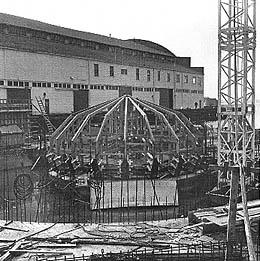

One solution was to place a planned "undersea" viewing dome in its own tank. Although visitors may think they have descended beneath Elliott Bay's waves, they are actually poised above within in a concrete and glass bubble submerged in a large circular basin.

The new Aquarium also included a fish ladder by which hatchlings could return to their birthplace. The route zigzags up its waterside face. Happily, the Aquarium welcomed back its first salmon in 1979, just a year after it opened to the public.

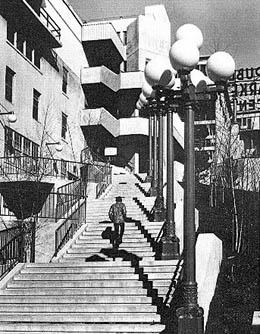

The Aquarium was a big hit with visitors beginning with its opening on May 20, 1977. Two related public improvements helped to lead visitors to its door. First was the Pike Place Hillclimb, championed by City Development Director and future mayor Paul Schell, and completed in 1978.

A second boost was received in realization of Seattle City Council Member George Benson's dream of a "Waterfront Streetcar" service, shown here in front of the Seattle Aquarium on its inaugural run in May 1982.

The Seattle Aquarium continues to educate and entertain visitors nearly a quarter of a century after its construction, but early compromises and time have taken their toll. The debate has begun on where, when, and how to take the next step to provide the region with a worthy aquarium while preserving the historic and functional character of Seattle's central waterfront. In short, this is the end of the show -- but not of the story.

Licensing: This essay is licensed under a Creative Commons license that encourages reproduction with attribution. Credit should be given to both HistoryLink.org and to the author, and sources must be included with any reproduction. Click the icon for more info. Please note that this Creative Commons license applies to text only, and not to images. For more information regarding individual photos or images, please contact the source noted in the image credit.